|

NSW Police Gazette

The description fits

Fred Lowry

& Ben Hall. |

The exploits of the Weddin Mountains gang, led by Ben Hall and his associates, captivated New South Wales, transforming bushranging from mere lawlessness into a public spectacle. In Sydney, newspaper editors eagerly awaited dispatches from rural correspondents, who, embedded within their communities, meticulously tracked the movements of both the outlaws and the police. The fierce competition among publications to deliver the latest, most sensational updates on the gang’s activities drove newspaper sales, as city readers devoured these thrilling accounts with fascination.

Like the police, these correspondents struggled to keep pace with the gang’s rapid movements, making it difficult to ensure their reports remained accurate amid shifting alliances and chaotic events. Crimes were frequently misattributed to Frank Gardiner, even though Hall, Gilbert, O'Meally, and Lowry had taken command of bushranging in the region. The overlap between their operations and past crimes associated with Gardiner only deepened the confusion over the true perpetrators.

Even after Gardiner fled New South Wales in October 1862, his legend loomed large, and he continued to be erroneously linked to fresh crimes committed by his former comrades. Reports of his supposed involvement flooded the newspapers, with victims and witnesses convinced they had encountered the infamous bushranger. The media, enthralled by his enduring notoriety, often speculated how Gardiner could seemingly be in multiple places at once.

This phenomenon was likely fueled by both the enduring fear of Gardiner’s name and the tendency of victims to attribute their misfortune to a figure of such legendary status. Even Sir Frederick Pottinger, well aware that Gardiner was no longer in the district, found his investigations hampered by persistent yet unfounded sightings. These repeated misidentifications only further entrenched Gardiner’s myth, solidifying his place in the folklore of Australian bushranging.

|

The Shamrock & Thistle Inn

Bowning was built in 1840.

One of the many hotels

the Gang frequented.

Private Source. |

Very little authentic information has recently been current respecting the movements of Gardiner and the more notorious characters with whom he is associated. Almost the last scrap of news apprised us that the "General," and Johnny Gilbert were scouring the bush near Jugiong, after having stuck up Mr Barnes' store, an account of which outrage appeared on the 29th April in our columns. On Wednesday last, Gardiner, in company with Lowry, Johnny Gilbert, and O'Meally, again appeared upon the scene, and, as far as it is prudent to enter into particulars, the following are the circumstances connected with their appearance:- It would seem that a little before daylight on the morning we have mentioned, while the Gundagai mail was near Bowning, four men, well mounted, and equally well-armed, passed through the township at a leisure pace, and owing to their appearance those who saw them considered that they were a party of police on patrol. The same horsemen subsequently passed the Binalong mail before it reached Bowning on its upward journey, and in the vehicle there happened to be a passenger who well knew the four equestrians, whom he at once recognised as Frank Gardiner, Gilbert, O'Meally, and Lowry. The horsemen passed on without interrupting the progress of the mail but were sufficiently near to enable the passenger, who had upon a previous occasion been stuck-up by Gardiner and Gilbert, and who knew the other two equally well by sight, to recognise and identify the four men beyond all doubt. On the arrival of the mail at Binalong, information was given to the police, and the word was passed on to Murrumburrah and Lambing Flat for troopers. Senior-sergeant Brennan, with constables O'Mara and Costoley of the police stationed at Yass, on receiving intelligence of the circumstance, started off for the purpose of scouring the bush. Since then many rumours have been afloat, to most of which we should be sorry to give currency. It is, however, generally believed that the four horsemen were seen near Yass, subsequent to meeting the Binalong mail. All the men are described as being mounted on fine upstanding horses, admirably fit for speed and endurance. At the offside saddle-bow of each a double-barrelled gun was slung with the muzzle resting in a leather bucket, and in each man's belt was a brace of Colt's revolvers. Gardiner is described as being dressed in a drab coat, the same coloured hat, and Napoleon boots.¹⁰²

|

Fred Lowry.

Penzig. |

The legend of Frank Gardiner remained deeply entrenched in the public consciousness, continuing to shape media narratives long after his departure from New South Wales. Even as Ben Hall’s gang terrorized the Yass district—following the audacious robbery of Inspector Shadforth on May 9, 1863—the press remained fixated on Gardiner, often at the expense of accurately portraying the true perpetrators of the region’s crimes.

Leading the police response, Senior Sergeant Brennan exemplified law enforcement’s determination to bring Hall and his associates to justice. Yet, despite these efforts, newspapers perpetuated the myth of Gardiner’s ongoing influence, his name frequently and erroneously linked to fresh acts of bushranging.

Unbeknownst to the public, "The Darkie" was, by this time, far removed from the chaos attributed to him. Residing in Apis Creek, Queensland, he had effectively severed ties with his former comrades, leaving Hall, Gilbert, and O’Meally to carve their own path of infamy. Still, the media’s obsession with Gardiner ensured his name overshadowed those actually responsible for the wave of crime sweeping the region.

A striking example of this misplaced focus appeared in the Empire newspaper on May 19, 1863. While the report detailed the relentless pursuit of Hall and his gang, it also—perhaps inadvertently—shed light on the immense physical toll endured by officers like Brennan. Tasked with tracking elusive bushrangers across harsh, unforgiving terrain, these policemen battled exhaustion, exposure, and the ever-present threat of deadly encounters. Their unwavering commitment to upholding the law underscored the immense challenges of policing Australia’s rugged frontier.

This era in Australian history was shaped as much by media-driven mythology as by actual events. The interplay between sensationalized newspaper accounts, public perception, and the stark realities of law enforcement blurred the lines between legend and truth, ensuring Gardiner’s name remained synonymous with bushranging—even when the true outlaws had long since moved beyond his shadow.

On last Wednesday afternoon, says Saturday's Yass Courier, "Senior-sergeant Brennan, accompanied by constables Mara and Hale, returned to Yass after a week's search for Gardiner, Lowry, Gilbert, and O'Mealey, whom we reported as having been seen early on the morning of the previous Wednesday on the Port Phillip Road, near Bowning Hill, The police at Yass first received information late in the evening of the last-mentioned day, and early next morning started in the direction of the place where the marauders had been seen. The bush in the direction of Wargiela and the neighbourhood was well scoured but without any trace of the wanted parties. A clue, however, was at last obtained, and there remained then no doubt that the four bushrangers had after meeting with the Binalong mail turned off under Bowning Hill, passed at the back of Mr Cusack's, Belle Vale, made the Yass River and crossed not far from its junction with the Murrumbidgee.

The police after making some necessary arrangements for the pursuit, took the course which had been disclosed by the information received, crossed the Murrumbidgee, touched on the Coorradigbee and well searched the country towards Tumut. From thence they in part retraced their steps, crossed the river near Taemas, and obtained a clue that the fugitives had been seen twenty miles ahead of them, making towards Queanbeyan. To that direction, the sergeant and his party directed their chase and followed it to the borders of Jingery, where the trace was lost.

Unfortunately, Mr Brennan had by this time become almost perfectly blind from exposure to the humid night atmosphere in the ranges but luckily met with Captain Battye with a party of police and two black trackers who were prepared to follow the scent. After the second time that the Murrumbidgee was crossed, Mr Brennan could learn at various stages confirmatory statements of the passage of the bushrangers, although acting with great caution they avoided calling at any places for refreshment. They were provided with hobbles, quart pots, and provisions, travelling by night, and camping in some secluded spot by day. At several places, the police came upon their camps and found the remains of a repast, with tracks of four horses having been turned out in hobbles. As the pursuit was taken up and will be followed in earnest, it is probable that it will not turn out fruitless. Considering the great difficulties encountered and the scant information which kept up the thread of the tracking, Sergeant Brennan and his party are entitled to much praise for their perseverance and ingenuity. They returned to Yass by the way of Bungendore, Brookes' Diggings, and Bungonia.

However, on this occasion, Brennan's pursuit was significantly off target. Ben Hall had double backed and reappeared in the vicinity of Cootamundra.

Interestingly, the implementation of a new method for cash transfer, known as the "Money Order System," was beginning to gain widespread acceptance.

The increased action of the Money Order Office in the interior is already telling against the trade of highwaymen. People travelling on the roads do not carry so much money with them in cash as they used to do.

During the height of Australian bushranging, the relentless pursuit of justice was the foremost duty of law enforcement. However, the substantial financial rewards offered for the capture—dead or alive—of notorious outlaws introduced a powerful additional incentive. For many police officers, these bounties far exceeded their annual salaries, presenting a life-changing sum that could drastically improve their circumstances.

This intersection of duty and financial motivation was exemplified in the career of Senior Sergeant Patrick Brennan of the Yass police station. Brennan’s unwavering dedication to law enforcement was prominently highlighted in a report dated May 21, 1863. Just months earlier, in February, he had gained recognition for killing a bushranger—an act that not only solidified his reputation but also earned him a considerable reward. This success likely bolstered his resolve, as well as that of his colleagues, in their relentless pursuit of other notorious figures, including Ben Hall.

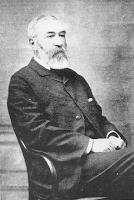

|

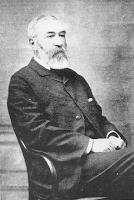

Sub Insp Brennan

c. 1870's.

Penzig |

The incident involving Brennan, reported

from Yass on February 28, 1863, vividly illustrates the high-stakes

nature of bushranger pursuits. Law enforcement officers faced immense

risks, yet for those who succeeded in capturing or eliminating these

outlaws, the rewards were both professional and financial. The

reliance on bounty incentives during this era added a layer of

complexity to police motivations, blurring the lines between duty,

ambition, and personal gain. Amid one of the most turbulent periods

in Australia’s colonial history, justice was often pursued not only

as a matter of principle but as a means of survival and advancement.

Saturday, evening, two bushrangers went to a public-house a few miles from this town, last evening; with a view of rifling it. Sergeant Brennan happened to be at the house. The bushrangers recognised him and attempted to get-away. Brennan fired on them and shot one dead. Subsequently, he captured the other and brought him to the lock-up today.¹⁰³

Sergeant Patrick Brennan of the Yass

police station was widely regarded as a stern and uncompromising

lawman, his reputation for no-nonsense enforcement well established

long before his lethal engagement with a bushranger. Brennan’s

rigid approach to maintaining order was exemplified in an incident

outside the Telegraph Inn in Yass, where he confronted a man named

Coady.

Accusing Coady of

idleness and loitering, Brennan, intolerant of perceived misconduct,

struck him with a forceful blow, sending him sprawling to the ground.

This episode, emblematic of Brennan’s unyielding stance on

discipline and authority, further reinforced his reputation as a

formidable enforcer of the law.

His actions, both in

this instance and throughout his career, cemented his image as a

resolute and decisive officer—qualities that, while controversial

by modern standards, were considered essential in an era of rampant

lawlessness and the rise of notorious bushrangers. Brennan’s

unwavering methods reflected not only the harsh realities of frontier

policing but also the prevailing attitudes of law enforcement during

one of the most turbulent periods in colonial Australia.

Coady began to talk big about his prowess, delicately apprising the police that on two occasions, while at home, he had dispatched a "peeler" to his long home; and afterwards expressed a desire to give Sergeant Brennan "a throw for a pound." Brennan, happening to be in the humour, accepted the challenge. Mr Coady found that he had pitched on the wrong man, the sergeant doubling him up "like a cod in a pot" in the course of a couple of minutes. Thus ended a case of misleading the police and its consequences.¹⁰⁴

Sergeant Patrick Brennan, a name

synonymous with unyielding law enforcement in bushranger-infested

districts, was not alone in his pursuit of outlaws. Among his most

valuable allies were the Aboriginal trackers, whose unparalleled

skill in reading the land and following trails proved indispensable

in the relentless hunt for fugitives. One such tracker, Billy Dargin,

earned widespread recognition for his extraordinary ability to trace

and capture criminals, securing both substantial rewards and the

respect of law enforcement.

Brennan’s formidable

reputation preceded him, making him a feared adversary among

bushrangers, cattle thieves, and troublemakers alike. His relentless

and often aggressive approach to policing cemented his status as a

ruthless enforcer of the law. Locally, he was both respected and

feared, earning the formidable moniker of the "fire-eating

little devil."

His commitment to

maintaining order was not only acknowledged but handsomely rewarded,

as evidenced by the bounty he received following a particularly

fierce confrontation with a bushranger. This payment was more than a

financial incentive; it was a testament to the dangers and demands of

frontier law enforcement—a profession where courage was paramount

and survival never assured.

Brennan’s career

epitomized the harsh realities of policing during the bushranging

era. It was a time of constant threats, where law enforcers had to be

as fearless as the outlaws they pursued. Through his actions and the

reputation he forged, Brennan became a defining figure in the

struggle to impose order on the untamed Australian frontier.

Senior Sergeant Brennan, of Yass, who has recently displayed great activity in apprehending a number of desperate characters, has been presented by the Government with the sum of £20 ($1680 today) from the Police Reward Fund, in acknowledgement of his services.¹⁰⁵

|

Painting, Yass township

c. 1854,

St Clements Anglican Church

foreground.

Note, no spire,

it was added in 1857.

Rossi St looking SW. |

Sergeant Patrick Brennan’s career in

law enforcement epitomized ambition, resilience, and success within

the ranks of the police force. His rise through the hierarchy was

fueled not only by relentless dedication and courage but also by the

tangible rewards of promotion—prestige, increased authority, and a

substantial salary boost. Advancing to the rank of Sub-Inspector,

with a salary exceeding £300 per year, was no small feat in an era

when such earnings conferred both financial security and social

standing.

Brennan’s ascent

from Sergeant to Sub-Inspector was marked by a series of bold and

decisive operations against bushrangers and criminals who terrorized

the frontier. His unwavering commitment to justice, coupled with his

relentless pursuit of lawbreakers, set him apart within the force.

His promotion was a testament to his tactical acumen, fearless

resolve, and the respect he commanded among both his peers and the

public.

Beyond personal

accolades, Brennan’s career became a beacon of aspiration for his

fellow officers. His ability to rise through the ranks, despite the

dangers and hardships of policing the Australian frontier, set a

precedent for others seeking advancement. His legacy was not merely

one of personal achievement but of inspiration—encouraging future

generations of law enforcement officers to embody the same tenacity

and dedication in upholding the law.

At a time when the

line between order and lawlessness was often perilously thin, Brennan

stood as a steadfast symbol of justice—a lawman whose name became

synonymous with the determined fight against bushranging in colonial

Australia.

We understand that the Government, having taken into consideration the conduct of acting sub-inspector Brennan in the apprehension of bushrangers of late, have promoted the officer named to the rank of sub-inspector, with the fall pay attached to that rank, as a mark of the Government's appreciation of the zeal and bravery displayed by Mr. Brennan on the occasion above alluded to. This mark of approval, in addition to the large reward that will be paid, by permission of the Government, to the officer named, will, doubtless, have the effect of stimulating every member of the police force to use the almost exertions to distinguish themselves in the detection and suppression of crime.

|

'Old Tom' Gin.

A favourite of the

1860s. |

In the perilous and unpredictable frontier of bushranger-infested territories, law enforcement officers operated under extreme stress. The looming threat of a violent confrontation with notorious figures like Ben Hall and his gang weighed heavily on their minds. The relentless nature of the pursuit, combined with the isolation of their postings, took a psychological toll on many officers, some of whom sought solace in alcohol—sometimes with unintended, and even comical, results.

One such incident, reported by The Sydney Morning Herald on May 25, 1863, involved a pair of troopers whose indulgence in alcohol led to exaggerated tales of their supposed heroics. Emboldened by their intoxication, they spun grand narratives of dramatic shootouts with O'Meally and Ben Hall, boasting of their fearless bravery and fierce gun battles that left their barrels smoking.

However, upon closer scrutiny, their grandstanding was exposed as pure fabrication—products of inebriated imagination rather than actual events. Their claims, meant to bolster their reputations, instead became the subject of ridicule, serving as a stark reminder of the psychological strain officers endured while patrolling the bushranger-plagued frontier.

While humorous in hindsight, the episode also shed light on the very real pressures faced by these men. The need to maintain an image of unshakable courage, coupled with the ever-present fear of bushranger attacks, created an environment where bravado often masked deep-seated anxiety.

This incident, though an amusing footnote in the history of bushranging, revealed the human side of law enforcement—men tasked with upholding the law in an era of violence and lawlessness, yet not immune to fear, self-doubt, and the occasional need to embellish their exploits in an effort to reaffirm their place in the ongoing struggle for order.

The other day, according to the Lachlan Miner, Neilson and Chambers, both troopers, were brought up at the Police Office, Forbes, by Sir Frederick Pottinger, on a charge of misdemeanour, and laying wrong information to the police. Sir Frederick Pottinger deposed that the prisoners started from the Forbes barracks on Friday last for Eugowra, a distance of twenty-six miles, to meet the escort; and on Friday night, between half-past nine and ten, prisoner Chambers rode up to his (Sir Frederick Pottinger's) quarters, and informed him that, as he and prisoner Neilson were riding between Roger's public-house and Eugowra, Neilson being about 100 yards ahead, he heard from fifteen to twenty shots; he rode up as quickly as he could, but his horse being fagged, he could not get him beyond a walk; he saw no bushranger, but Neilson's horse was bleeding from wounds on the neck; Neilson told him that five armed bushrangers had asked him for his jacket, and he (Neilson) had, of course, refused; one of the bushrangers then said, " I'm ------ if you take that horse into town," and fired; Neilson then exchanged shots with them. Chambers further reported to Sir Frederick that he had found traces of blood close up to the Southern Cross, and prisoner stated that he believed two of the men to be John O'Meally and Ben Hall, and concluded by expressing a hope that he would be kept in the district, as he would like to have a go-in at the rascals. The prisoner had evidently been drinking, and he was told to hold himself in readiness to accompany the police out when the moon got up. About one o'clock Mr. Sanderson, two troopers, the tracker, and the prisoner Chambers were sent in the quest.

Mr. Sanderson returned the same night with the prisoners, but without any information about bushrangers. On the information of Chambers, Sir F. Pottinger deposed to dispatching orders to Bogobogolong, the Pinnacle, and other police stations, which orders, on the return of Mr. Sanderson, had been cancelled. Prisoner Neilson here stated that he was drunk at the time, and he did not know what he was doing. Prisoners were at this stage remanded for three days. Bail allowed themselves in £80 each, and two sureties in £40 each. This case (adds the Miner) appears to have arisen out of a love of nobblers and the chase. Mr. Neilson, who rode a good horse, saw an emu, and feeling in himself equal to anything, he turned and fired at the bird. An unsteady hand, however, caused the bird to escape, and the charger to suffer. We hardly know which most deserves trouncing- the emu-shooter or his mate, who came to Forbes and told the lies for him.

|

John Chamber's police

employment and

dismissal. |

The sensational encounter between officers Neilson and Chambers and the alleged bushrangers O'Meally and Hall sparked considerable discussion and speculation. Yet, the tale took an amusing twist when it was revealed that the suspected 'Emu' involved in the chase was in fact a local pet. This intriguing detail was recounted in the 'Bathurst Free Press' on 16th May 1863, which published a detailed account of the events involving the notorious winged bushranger.

According to the account, the gunfight was as thrilling as any, filled with smoke and daring chases, and narrow escapes. However, the revelation that the Emu was a well-known local pet added a dash of comedy to the otherwise tense narrative. In an attempt to flee, the pet Emu had become entangled in the chase, causing some confusion and ultimately aiding in the 'bushrangers' escape.

This unexpected twist in the story served not only to entertain the public but also to highlight the unpredictable and often chaotic nature of police attempts to apprehend the elusive bushrangers while under the influence. As law enforcement continued their pursuit, stories like these served as a peculiar and humorous aside to the harsh reality of bushranging during this period.

The following is on extract (kindly handed to us for publication) from a letter received by a gentleman in Bathurst. It is a fine illustration of the fitness for duty of the officials to whom the protection of our lives and property has been committed. The incidents related are amusing, but there is something in the concoction about the bushrangers which disposes us to treat it with ridicule. Had the affair ended with an escape from the attack of their long-legged visitor, we might have looked at it in the light of a good joke, and have spoken of it accordingly; but when well-mounted troopers, armed at every point, convert a pet emu into eight bushrangers, and a journey of fifty miles is undertaken for the purpose of depriving honest men of their liberty, it goes beyond a joke, and ought to draw the attention of the authorities for the purpose of investigation. "Joe," the hero of the tale, we ought to remark, is a large pet emu belonging to the brother of the gentleman who has favoured us with the extract, which is as follows: -"Joe (the Emu) has had a great lark and tremendous battle, in which he has come off victorious. He followed the bullock driver when out looking for bullocks; when they got to Marara Plains they saw two policemen, whose white caps and shining accoutrements attracted Joe's attention so that he made up to them for inspection. The police charged him when the bullock driver called to them not to hurt him as he was my pet emu; if they heard, they did not heed, and one of them fired, Joe, did not mind the report, as he is well used to the cracking of stockwhips, he kept on running close to their horse’s heads; - two other shots were fired, with the same effect, so far as Joe was concerned, not so the constable's horse, the last ball having taken effect in his neck. The two policemen came to their barracks much excited, saying that they had been attacked by eight bushrangers, who had shot the horse, one of them galloped to Forbes (nearly 36 miles), and reported the attack. Four troopers came out, but the yarn was too lame, added to which the bullock driver and Billy Lambert saw the whole fun. When he heard the story he went to inquire the truth of the matter and saw the mark of the powder on the horse's mane and neck. The men were both arrested and taken to Forbes. No doubt they would have sworn to the tale of the bushrangers if it had not been proved to the contrary. "Joe" came home this morning as well as ever.

Both troopers were dismissed from the force.

|

Inspector Sanderson

c. 1896 |

The ever-present threat and anticipation of encountering Ben Hall and his associates led to a mounting sense of tension and frustration among the police force. Even the most respected officers were not immune to these pressures. This was exemplified in an incident that occurred in June 1863 involving the well-regarded 'Hero of Wheogo', Inspector Sanderson.

Mrs Allport, who owned a lodging house in Forbes and had formerly operated Allport's shanty, where Daley and Hall had been pursued by Constable Hollister and Billy Dargin in February 1863, lodged a complaint against Inspector Sanderson. She alleged that Sanderson had unlawfully broken into her home, physically harassed her tenants, and caused damage to her property.

Mrs Allport, who was known to have had previous dealings with Ben Hall, represented one of many challenges that law enforcement officers faced in their pursuit of the bushrangers. These complications, combined with the constant threat of encountering Ben Hall and his gang, created an environment of high stress and pressure for the police. As a result, even highly esteemed officers like Inspector Sanderson found themselves in situations that tested their judgement and conduct. The incident was reported in 'The Lachlan Miner' on 24th June 1863:Note: A criminal offence consisting of accepting a reward or other consideration in exchange for an agreement not to prosecute or reveal a felony committed by another. Compounding a felony is encompassed in statutes that make compounding offences a crime.

However, after the robbery at M'Connell's, Ben Hall boasted that:

They did not fear the police who they said, we're afraid of them and declared that they would never be taken alive, in their own words, that, as they knew they would have to swing-when taken, they would sell their lives as dearly as possible.¹⁰⁶

|

NSW Police Gazette

11th June 1863. |

Indeed, having siblings or close family members in the area would have provided Ben Hall with an additional layer of support and protection. Although there is no record of Robert Hall's direct involvement in any of Ben Hall's bushranging activities, his presence in the area during Ben's criminal activities may have been a source of familial support or perhaps even an attempt to persuade his elder brother to abandon his life of crime.

In the same area, the presence of his other brothers, William and Thomas, might have further offered Ben Hall aid or at least a form of passive support by providing information about the police's activities or other useful intelligence.

However, it is also worth noting that family members might not have approved of Ben Hall's criminal lifestyle. It's entirely possible that their presence was a source of tension, as they may have attempted to convince Ben to cease his bushranging activities.

In many ways, the involvement or presence of family members could have added another layer of complexity to Ben Hall's life as a bushranger. They might have provided support, but they could also have been a source of potential risk if they chose to cooperate with the authorities or if they were targeted as a means of reaching Ben. The reality of the situation likely falls somewhere in between these scenarios, with the relationships between Ben Hall and his brothers characterised by a mix of familial loyalty, personal conflicts, and practical considerations related to survival.

Robert had been released from Maitland Gaol after serving a six months’ sentence for:

Illegally using 2 bullocks the property of Alexander Brodie J.P. and Fred White J.P.

|

| Robert Hall Maitland Gaol Entrance Book December 1862 |

|

| Police Gazette, the horse, stolen by Robert Hall. |

|

John Gilbert

c. 1861.

Coloured by me. |

An article appeared in the 'EMPIRE' covering the latest in bushranger atrocities in the Young District where once more the correspondents were incredulous at how easy Ben Hall moved from one business robbery to another, June 9th, 1863:

Bushranging has again appeared in all its pristine vigour and reckless audacity. Unmolested, proceeding down the Main Creek to Heffernan's public house, where they had drinks, taking with them a revolver, a silver watch, and seven bottles of brandy. They then visited Regan's Hotel, near White's station singing as they approached the house, the very appropriate song of O'er the hills and far away.

Such is a true and correct account of this said, of which I was, as far as the Flat is concerned, an eye witness. The camp being less than one mile from the scene of this outrage, a body of police arrived about midnight, being nearly an hour and a half after the robbers had decamped, (a strong proof of their alacrity and usefulness,) expressed their wonder at the bullet holes through the store. Looked for foot-prints, asked a lot of stupid questions, accompanying them with a sapient nod or a cunning look, but never attempted to move one step in pursuit of the ruffians. Why in heaven's name are the people of the colony taxed heavily to support such a useless, stupid, herd of fellows? On the Monday previous, Gilbert and Co., as I informed you, stuck up two stores, not one-quarter of a mile from the camp, now they plunder four stores, and several men, less than one mile, and ride off with their booty without the slightest attempt being made to pursue them. That clever detective, Inspector Singleton asked why did not the miners keep fire-arms, and use them on the bushranger’s when they paid a visit, but never attempted to do what a man would do, follow them. We have been promised for some time back great performances by the police, well-laid traps were being laid for the various gangs who infest the district; the police were gradually but surely "hemming them in," and in a few weeks would show what a plover fellow Superintendent Zouch was; when the word bushranger was used in the presence of the police, it was sure to evoke an expressive wink or a sapient nod. But this pitiful humbugging has been rudely exposed, and the glorying incompetency of the present police force to repress this species of crime by the outrages committed by the gang of ruffians under the leadership of Johnny Gilbert.

|

Goldfield miners meeting.

c. 1863.

Courtesy NLA. |

Does it require more lives to be sacrificed ere the people of this district obtain that security for life and property which should be characteristic of every British community? I tremble for the consequences of another murder such as Cirkel’s. Retribution will follow that will strike terror to the heart if every ruffian who has outraged law and society, for the last eighteen months with impunity. The pent-up indignation of an outraged population will rush forth in such a stream as will carry before it the feeble barrier now existing between constituted authority and Judge Lynch. I will say no more, but utter a solemn warning to the Government, to be warned in time to take proper measures for the repression for this tide of crime before it is too late. A very cheap offer to capture Gardiner, Gilbert, and the other less distinguished members of this firm, was made by a goldfields official, whose plethora of pluck led him to accompany that brave body of police who visited the scene of action. The following is the offer verbatim-"I am a 72-inch native. If the Government will give me £1000, I will resign my gold commissionership, and guarantee to hand Gardiner over to them in one month, the others to soon follow. I recommend this cheap offer to the earnest consideration of Mr Cowper, as an easy way of ridding himself and us of so great an annoyance. I can give no guarantee, but I hope his native youth will not be like a Pottinger, a Norton, or Shadforth, great in words but contemptible in deeds. At all events as his energies appear to be misdirected, why not transfer him to the police force station, at the Weddin Mountains, and let him try his hand at thief catching.¹⁰⁷

(See Gallery page for the song or click the link below, a fun ditty.)

|

NSW Colonial Secretary

Charles Cowper. |

However, the Cowper Government, already facing no-confidence motions in the NSW Parliament regarding the struggling reforms of the new Police Act of 1862. Included accusations over financial mismanagement. Mr Cowper faced the June 1863 Parliamentary Sessions under close scrutiny. The press also continually harassed the government and brought the question of settler safety to the forefront of the public mind.

Ben Hall, Gilbert and O'Meally, with Gilbert reported to be leading the trio, appeared nonplussed over the government's difficulties and attempt to seize them and continued to ride roughshod over the small towns and outlying stations procuring all that they fancied day and night. Satisfied in their work, the bushrangers holed up for days at the homes of many friends, only too willing to offer them a safe harbour. For an innocent local, just going about the countryside in 1863 was fraught with danger:

THE approaching session of Parliament is no doubt looked forward to with great interest by an important section of the community the gentlemen with grievances. Prominent among these stands the people of Burrangong. For many months past, they have almost enjoyed a monopoly of the terror and panic created by the bushrangers. The place seems to have become the headquarters of all the ruffians in the district. Making every reasonable allowance for exaggeration in the reports which have poured in upon us, there remains no room to doubt that life and property are utterly insecure. The most audacious outrages are still committed with impunity. There is hardly a store which has not been plundered. None of the ruffians who have gained so much vile celebrity has yet been brought to justice. The promise of their bright career remains as fresh and cloudless as ever. A short time ago, we were told that the Government was in motion at last and that the fate of these scoundrels was decreed. Troops of police were to be despatched at once, and the whole district was to be effectually cleared. Days and weeks, however, have rolled away, and things remain just as they were. The police are as powerless, the bushrangers as bold and daring as ever. The local paper informs us of a series of outrages which, after all, that has been said, may fairly be considered startling.

This is a frightful state of things; We appear to be surrounded by these desperadoes; the roads, in all directions, are infested with them; safe travelling is almost impossible; life and property are insecure; the business of all kinds will, ere long, be completely paralysed; and what is done will have to be confined to the township alone. If this is to be the result of the famous New Police Act, the sooner it is repealed the better, for it appears to be a curse instead of a blessing to the colony. The ridiculous, military parade attached to it is looked upon with contempt. We do not attach the blame to the police. They are obliged to obey the orders they receive and do their duty. Even supposing they captured any of these noted robbers, the reward does not go to the individuals, but to the police fund. The heavy expense of the prosecution in attending the Criminal Courts, either in Goulburn or Sydney, fall upon them, for out of their small pay they must disburse it. The time has now arrived when some alteration in the police system must be effected. It is scarcely, necessary to add any comments of our own to this. At the outset, we prophesied the failure of the New Police Act. Every incident in connection with it has conspired to expose its fallacy. Eighteen months have now elapsed. We were told that the new system required time in order to develop the full bloom of its beauty. It has had time enough. There is nothing which can be urged in its favour, we trust, for the credit of the colony, that the approaching session will witness a radical alteration in its provisions.¹⁰⁸

Furthermore, on information the police received of bushranger activity through their sources, Inspectors arrived at various towns not only in pursuit of the criminals but for the town social functions. These events were predominately horse race meetings—Ben Hall and John Gilbert's known favourite pastime. Horse races throughout Australia were exceptionally well attended, with local citizens pouring onto the bush tracks. A welcome distraction from the mundane life of bush settlements or remote farms.

The events often ran over three days with different monetary purses up for grabs, some above 100 guineas (£210). The highlights of these well-attended meetings were the popular one on one races between local champion horses with side bets abounding. The festivities didn't end at the track with evening dancing, dinners and ale's flowing.

It was, as well, a chance for the ladies to adorn their most elegant fashions. Not only locals turned out, but the bushrangers arrived incognito in search of prospective thoroughbred mounts or to place wagers and enjoy their notoriety shielded from police by those who held sympathy towards them. For John Gilbert, the races were a chance to wear his most stylish female attire as a disguise. As reported:

Gilbert, it is well known that he attended the last Young races, mounted on horseback, disguised in a lady's riding habit, hat and feather. His smooth, good-looking face much assists him in this respect.

However, in hope of securing the bushrangers, the police also checked in as well, and in many cases, acted as race stewards and officials. Sir Frederick Pottinger was one such officer who would not let a good race meeting pass him by. Arriving at one such event at Lambing Flat simultaneously as the bushrangers were looting some of the local stores; 'Empire', 13th June 1863. However, for Sir Frederick, the love of a good race would in the future, cost him dearly:

The three days races passed off very quietly, although the sport was very fair, and the attendance pretty numerous; yet the scarcity of money threw a damper on that hilarious spirit so necessary to enjoy a race meeting. Sir Frederick Pottinger, as usual, created much amusement by appearing on the racecourse with blankets, strapped on before him on the saddle; a quart pot, a pair of hobbles; and a pair of handcuffs, being artistically arranged around other parts of his saddle. His man Friday, in the shape of a black tracker, followed him. The who o, to use a much-hackneyed phrase "forming a unique sight which must be seen to be fully appreciated.

Ridicule of the good inspector was ever-present since the fiasco with Gardiner at Kitty Brown's in 62.

Furthermore, race meetings aside, the Australian bush for the uninitiated was an unforgiving environment. Whereas for the native-born Australian bushranger, the landscape was hearth and home. However, many police were recruited from Ireland and England. Therefore, the Australian bush for those men could be an unrelenting nightmare. Police recruits were also drawn from as far afield as America and Canada. As a result, these raw immigrants were often referred to as new chums. For some troopers, their bushranger work in an unfamiliar scrub cost them their lives as they succumbed to impenetrable hills and valley's or while fording flooded streams. 'The Sydney Morning Herald' Wednesday 4th March 1863:

On Wednesday last a trooper, named Jeremiah O'Horregan, was drowned in the Lachlan River, in the immediate vicinity of the baths. Deceased had been on special business, and was returning from the Weddin Mountain to Forbes. On reaching the crossing-place at the Lachlan River, he found the river flooded; but, heedless of the danger of attempting to cross under such circumstances, he pushed his horse into the stream. It appears the horse was carried down a short distance by the current, when O'Horregan (who had very little experience in swimming a horse) checked his charger with the rein, instead of allowing it to make for the opposite bank, according to its own instincts. The result was the horse rolled over, and the rider was pitched into the river. O'Horregan, being unable to swim, sank immediately, and was drowned, notwithstanding the effort of a couple of blackfellows (who happened to be on the bank at the time) to rescue him. The body was recovered by the blacks about three hours after; and an inquest was held on Wednesday evening before D. W. Irving, Esq., where a verdict of accidentally drowned was returned.

The naivety of other migrants' understanding of the Australian interior's wilds was also prevalent, as these new chums often travelled alone through the bush from Goldfield to Goldfield, town to town and wrestled with the vast dryness or flooded plains and its dangerous creatures. It was, to say the least, intimidating. Inexperience could be life-threatening, as was the case of a migrant miner from a faraway land crossing from one digging to another who lost his way. From the 'Pastoral Times' 9th June 1863:

One of those too frequent cases, being lost in the bush, occurred some short time since beyond Booligal, on the plain between the Lachlan and Murrumbidgee rivers. A few days ago, the police at Booligal received information that the remains of a man were found on the plain, on preceding to the spot the bones of a human being were found, with a Passport in the German language, and a slip of paper, on which was written in pencil, "Died want of water" It is supposed the unfortunate deceased attempted to cross from river to river, and perished in the effort for want of water, This sad result should be a caution to others not to venture beyond a certain distance on dry plains.

The same was said of the police as a newspaper observed of the lack of experience faced by the new Police of New South Wales up against those native youth 'Born in the Saddle':

The troopers are, for the most part, unacquainted with the country, as a rule, the men were not good bushmen, nor were they good Bush riders, in fact, unless men were trained to bush riding they would never be good at it, for it was a very different thing from riding in the streets of Sydney.¹⁰⁹

|

Robert's 'Currowang Station'

stables. c. 1863.

Courtesy Young Witness. |

Subsequently, for those new to the outback, death was everywhere. On the 18th June 1863, Ben Hall with John O'Meally stole the racehorse's Mickey Hunter and Chinaman from Mr Roberts' 'Currowang station'. Unfortunately for Mr Robert's over the next few years, he would receive numerous raids for good horses by the gang:

These lawless desperadoes are carrying on their depredations with such barefaced impudence in the district surrounding Lambing Flat, that people begin to imagine that the police endeavour to their utmost to avoid an encounter with them. The last exploit that has occurred, or rather that we have heard of, is the entrance of two of the gang, well-armed, upon the premises of Mr James Roberts, at Currawong, near Murrumburrah, on last Thursday evening, at seven o'clock. They forced an entrance into the stables and rode off with the race-horses, Mickey Hunter and Chinaman. It is only a short time since the latter animal was stolen and subsequently recovered by Inspector Shadforth. Gilbert seems determined to have his bodyguard well mounted.-- Yass Courier. (A telegram to Empire states that Sub-inspector Wolfe was in the house at the time the horses were stolen.) Mr Sub Inspector Wolfe was at the time enjoying his pipe and glass in Mr Robert's hospitable parlour, but, on the appalling discovery, he gallantly rushed out, and with the presence of mind equal only to the rashness of his valour-locked the stable door! Verily all our police Wolves are innocent Lambs!¹¹⁰

|

NSW Police Gazette.

1863. |

Having escaped with two valuable racehorses under the very nose of a visiting police inspector. On the 21st of June 1863, Ben Hall's associate, John Gilbert, was associated with murder. John Gilbert was named as an accomplice along with another of the gang, Fred Lowry. Gilbert and Lowry's heinous offence was the mortal wounding of a favourite miner named M'Bride, shot after M'Bride was mistaken as a police trooper:

It is with feelings of the deepest indignation and humiliation that I forward you the particulars of the outrage perpetrated on last Sabbath morning by those two archfiends Gilbert and Lowry, which, I regret to say, has resulted in the death of Mr John M'Bride, a highly respected miner resident on the Twelve Mile Rush. It appears that, while on his way to Young, and when near Duffer Gully, he was "stuck up" by Gilbert and Lowry and having, unfortunately for himself, a revolver with him, he showed fight, and sold his life bravely. He fired five shots at the two ruffians, but without any apparent effect; and, having but one more shot left, he made for a tree and stood his ground nobly. The bushrangers separated one each side of the tree, and fired nine shots at him, the sixth shot wounding him mortally in the thigh. Poor M'Bride still stood up, moving around the tree, marking his tracks with his life's blood, till, firing his last shot through Lowry's hat, he fell exhausted and dying. Gilbert then dismounted, rifled the dying man's pockets, and, taking his revolver, the two rode off, laughing.¹¹¹

|

Croaker's Inn, NSW Police

Gazette, 8 July 1863. |

A few days after, Gilbert and Lowry had mortally wounded Mr M'Bride, who died during a rough cart ride to Lambing Flat hospital in agony and suffering for many hours from the inflicted wounds. Gilbert, later at a shanty, attempted to sell the pistol of M'Bride's. However, there were no takers.

When informed that M'Bride was no policeman, a stunned Gilbert maintained that he shot at the man's pistol arm and hit him in a vital spot by accident. Gilbert is to have said afterwards:

I'm sorry for this, I've never wanted to kill a man, especially a brave bloke like this feller.

O'Meally was wrongly reported at the miner's confrontation. However, O'Meally was in company with Ben Hall on Sunday, 28th June 1863. The pair robbed Gordon’s coach at Croaker's Inn. (See right.) Next, they held up a shopkeepers boy:

A storekeeper's assistant was stopped while crossing the Main Creek, about half a mile from the town, about noon to-day by two armed men, well mounted. He was ordered to get off his horse and deliver up his cash.¹¹²

|

NSW Police Gazette

8 July 1863. |

On the 29th June, it was reported in the NSW Police Gazette regarding a perpetrator closely fitting Ben Hall's description, of being alone riding the stolen racehorse 'Mickey Hunter' and robbing an employee of Young storekeeper Miles Murphy of 11½ dwt of gold, a £1 note and 27s in silver. (see article left)

To disseminate the bushranger news effectively, the telegraph, much like the veins of a body carrying oxygen, issued instant reports of the bushrangers daring deeds. In an effort to thwart information of their operations, the bushrangers commenced cutting down the telegraph wires and the poles supporting them. For the first time, the bushrangers were taking an active part in limiting the new power of information reaching authorities. 'Sydney Mail', 4th July 1863:

Another precaution taken by the desperadoes on Sunday morning was that of cutting the telegraph wires which communicate with this district and the metropolis by way of Forbes, at a place about eighteen miles from Bogolong, and carrying away some portion of it, which accounts for my not getting my telegram through on Sunday; and there is no doubt that if the present state of things exists much longer telegraphic communication will be entirely stopped.

Furthermore, as alluded to earlier the bush telegraphs employed by the bushrangers were the primary source of information on the comings and goings of persons carrying valuables. Many storekeepers who traversed the country roads sweated on circumventing contact with Ben Hall and his mates whereby with the towns' remoteness and an inadequate police presence was worrisome. Many kept their movements secret. On top of that, many people searched for fellow travellers whose company often provided protection or, if very lucky, the possibility of them joining a police patrol heading their way.

It was reported of one such occasion, where a storekeeper from Lambing Flat had procured some gold at Wombat, a small settlement eight miles south of Young and faced a dilemma for his transit to Young and a safe return to his home. Luckily to his good fortune, a local police patrol appeared like saviours, and he immediately joined the troopers. However, a secret is only safe between two people if one of them is dead therefore for the traveller Ben Hall was undoubtedly appraised of the good shopkeepers' secret and movements, and his rich purse were with his mates in tow Hall waited near the road ready to pounce. For the traveller, the sudden police protection became invaluable:

About four days ago a certain Lambing Flat storekeeper went to Wombat to purchase gold; having been rather successful, he, under the existing state of the highway, naturally became anxious about his precious charge, consequently looked around for protection, when he, fortunately, espied trooper Murphy and three others proceeding towards Young. When near the Stony Creek, one of the police exclaimed: "By Jove there they are," looking in the direction pointed out, where, sure enough, were seen to be four bushrangers, viz., Gilbert, J. O'Meally, Lowry, and Hall. The rascals were on the side of a rather thickly timbered range, and were lying flat on their horse’s backs, gazing at their wished-for prey (the storekeeper) and, I've no doubt, licking their lips and cursing their bad luck and the escort. However, Murphy and his mates dashed at them helter-skelter, over hill and dale, the troopers occasionally taking a snapshot with their carbines. The police, being pretty well mounted, for the first mile-and-a-half held their ground bravely, but ultimately got distanced and had to pull up with their cattle completely blown. An eye-witness informs me that the pace of the bushrangers' horses was tremendous, particularly Gilbert's Jacky Morgan, which went like the wind.¹¹³

|

| 'The Darkey' |

By mid-1863, despite Frank Gardiner’s long absence from New South Wales, his name still dominated newspaper headlines. The press, unwilling to let go of his legend, treated his disappearance with the same gravity as the resignation of a high-profile CEO. In a tongue-in-cheek remark, the Illawarra Mercury framed the transition of leadership within the bushranging world as though it were a corporate reshuffle, noting that John Gilbert had been "promoted" to head of the gang’s operations in the South Western districts.

Having earned a notorious reputation as Gardiner’s trusted lieutenant, Gilbert’s ascension was inevitable in the eyes of the press. With Gardiner out of the picture, Gilbert seamlessly stepped into the role of heir apparent, his name now emblazoned across reports of audacious raids and highway robberies. The newspapers, ever keen to dramatise the bushranging saga, embraced the notion of succession, casting Gilbert as the new chief executive of lawlessness in the colony.

This exaggerated portrayal, while humorous, underscored the public's fascination with the outlaws who terrorised the goldfields and beyond. The transition from Gardiner to Gilbert was not merely about leadership—it was a reflection of how bushrangers had become larger-than-life figures, their exploits chronicled with almost theatrical flair by the colonial press.

It appears that the famous bushranger, Gardiner, has somehow backed out of his bushranging business, and retired from public life, leaving his associate Gilbert at the head of the concern. "Bell's Life" in Sydney, not unhappily hits off this change in the following notice:- "The public is respectfully informed that the partnership hitherto existing between Frank Gardiner, John Gilbert, and John O’Meally, 'Road Contractors,' trading in the South-Western districts under the style of 'Gardiner, Gilbert, and Co' was this day dissolved by mutual consent; and that the business will in future be carried on by the said John Gilbert and John O’Meally, as 'Gilbert and Company,' who will pay all debts of gratitude due by the late firm, and collect all outstanding accounts. In retiring from business, Mr Frank Gardiner begs respectfully to tender his acknowledgements to the Government for the 'liberal' measure of support (the new Police Act) accorded to him since he has been in business. Mr Gardiner has also to express his sincere thanks to his friends, the 'gentlemen' of the police, for patronage they have ('unwittingly') bestowed upon him, and solicits a continuance of that support for his successors, in whom he has every confidence that the business will be conducted by them with the same promptitude and energy that distinguished the late firm. "In reference to the above, Messrs. Gilbert and Company beg to assure their friends and the public generally that no exertion shall be wanting on their parts to merit a continuance of the confidence placed in the late firm of Gardiner, Gilbert, and Co. Messrs. Gilbert and Company respectfully announce that whilst diligently attending to the Mails, it will be their constant study to treat the females with every courtesy and gentlemanly consideration. "**Racehorses purchased or exchanged on liberal terms." N.B.-Gin, of the finest quality, supplied to travellers gratis. "Weddin Mountain, 6th July 1863.¹¹⁴

|

Mrs Hammond.

c. 1860. |

However, M'Bride dead. The suspected killer Fred Lowry quickly bolted back to his old haunts at the Fish River. Gilbert and O’Meally, without Ben Hall, ventured together further south to the small farming community of Junee 'Bailing-up' some shops and farms. The first Junee raid occurred on the 7th July 1863;

Gilbert and O'Mealley stuck up a store and public-house at Junee on Wednesday last. They got away with their plunder. The police are now in pursuit.

While the two haunted Junee a new player, unknown to the gang, named Daniel Morgan, commenced his appearance in the Wagga Wagga region. However, in a letter from one of the victims of Gilbert and O'Meally's foray, Mr Hammond wrote to the 'Sydney Morning Herald' outlining the events regarding their Junee robbery dated 13th July 1863. John Hammond wrote:

On Saturday, last Mr Gwyne, of the firm of Gwyne and Hammond, received from the latter gentleman a letter, in which he gave some particulars of the sticking up of a store at Junee, about twenty miles from Wagga Wagga, by Messrs. Gilbert and O’Meally. The letter is dated Junee, 7th July, and the passage referred to is as follows: -"It is but two hours ago, that the public-house store at Junee was stuck up by Gilbert and O’Meally, who robbed the place of goods and money to the amount of £50 or more. Mr Howell was also bailed up, and Albert just went to the store while they were there, and got bailed up too He, however, went outside and gave the robbers the slip, running down here as fast as he could. (Albert is the brother of John Hammond) We got a horse and started. I got two men, each armed with a gun, and we went up to see if we could take them; but we were too late, as, when they missed Albert, they galloped away. It being quite dark, they could not be followed till morning, when expecting the police will be too late. I got Arden to stop with Mrs H., while I was away, but she would, however, rather have gone with me.

|

NSW Police Gazette.

2 September 1863. |

I do not think they will visit us, but we are on the alert. These are the men who are supposed to have shot a digger a few days since at Lambing Flat. They are well mounted and do not seem to stick at anything. I hope they will be taken, as no one is safe in this neighbourhood. They searched Albert, but got nothing; it was fortunate they did not see him escape, or they would probably have shot at him.

|

Fred Lowry dead.

The photo was taken at

Goulburn Hospital. 1863. |

Moreover, after M'Bride died from his wounds, Fred Lowry shot through from the Lachlan. Lowry bolted back to his familiar territory, the Abercrombie District. It was the second time Lowry had drawn an innocent man's blood.

Upon returning, Lowry re-joined his old Abercrombie comrades Larry Foley and Lawrence Cummings. Shortly after, the trio made their way to the foot of the Blue Mountains, and on the 13th July 1863, robbed the Mudgee Mail making off with £5000 ($420,000) in cash. However, when Fred Lowry separated from Ben Hall, Gilbert and O'Meally it would be the last they would ever see of their compatriot, as within a few weeks after the Mudgee robbery, Fred Lowry would be cornered and mortally wounded by Senior Sergeant Stevenson on 29th August 1863 at Vardy's Inn, the Cook's Vale Creek. As Lowry lay dying and his lifeblood drained away, he wheezed the immortal last words! "Tell 'em, I died Game".¹¹⁵ (see Gang page.)

|

Lambing Flat Goldfield.

For enhanced view open

in New Tab.

Courtesy Young Historical Society. |

M'Bride's murder had instigated a sudden split within the gang. Accordingly, rumours of constant disagreements between Hall and Gilbert regarding operations or who was calling the shots spread. Either way, Ben Hall bid adieu, resulting in Gilbert with O'Meally going out on their own. However, in the wake of the recent M'Bride killing, it had made the area around Young, as it had become for Lowry, too hot for the two wild colonial boys. Therefore, they shifted their swag sixty miles east to the Carcoar area.

Arriving in the new operating area, Gilbert and O'Meally soon made their presence felt. The pair quickly sought out a local lad named John Vane, who was on the run and had been a former acquaintance of John O'Meally when stock-riding at the Weddin Mountains sometime earlier in 1861 was tapped on the shoulder to provide some help. As a consequence of renewing their mateship, Vane join-up with the two bushrangers and whose general knowledge of the surrounding countryside greatly benefited the two visiting bushrangers.

During the separation between Gilbert, O'Meally and Hall, Vane revealed in his biography that Ben Hall had moved to a locality outside of Young camping on a large sheep station named Mimmegong. When Vane eventually met Hall, he commented that Hall had him accompany him from Mimmegong to Young to retrieve some washing held at a lady's home:

Ben Hall asked me to accompany him to a place some miles distant, where he had left some shirts there to be washed, we rode there together and returned early afternoon.

Suffice to say, Ben Hall's former girlfriend Susan Prior and his daughter Mary, now almost five months old, had returned to Lambing Flat area with her mother Mary and younger sister Charlotte. Susan would, in due course, move to Burrowra.

When Ben Hall began a romance with Susan Prior her mother Mary had been in an abusive relationship with one George Pentrow. When the opportunity arose to flee the wretched man the women took the opportunity to live at Sandy Creek. However, with the home's incineration in March of 63, the women returned to Young and Pentrow was soon lurking. Unfortunately, Susan's youngest sister Charlotte, an eleven-year-old, was sexually molested by her mother's partner before their move and where terrified the young girl said nothing of the attack. However, upon revealing her violation George Pentrow was arrested on the 23rd of January 1863. Consequently, Pentrow was found Guilty and sentenced at the end of March 1863 to five years of hard labour on the roads. Pentrow had previously arrived from Hobart in company with Susan's mother. Upon sentencing, the judge commented:

|

| Pentlow. |

Upon the scandalous behaviour of the prisoner, and observed that, if he was not misinformed, he had been formerly convicted in Tasmania, and had obtained some remission of his sentence. He was a person not fit to be at large, and it was necessary he should be secluded from society for some considerable time. The sentence of the court was that he be kept to hard labour on the roads or other public works of the colony for the term of five years.¹¹⁶

For Charlotte, the horror of the events saw her take her own life at the age of 14 in 1864.

While Susan Prior was residing at Sandy Creek, her mother Mary had arrived with her unfortunate daughter Charlotte following the harrowing episode with Pentrow. The home also includes Susan's brother William. There were reports when the police believed that Ben's mother Eliza was living at Sandy Creek. Pottinger had attested, too, after the incineration of the home that left the women destitute. However, this was not the case!

The house was at the time occupied by Henry Gibson (notorious villain since committed), also illegally at large from Victoria, Mrs McGuire, and Hall's mother, and was daily frequented by bushrangers.¹¹⁷

Unfortunately, Pottinger's assessment was well off the mark as all evidence indicate Susan's mother Mary Prior was residing at Sandy Creek. No doubt to support Susan during the birth of Ben's daughter Mary in January 1863. During the trial of Pentrow, Mary Prior shed light on her knowledge of individual criminals stating that while living at Wheogo, she knew Ben Hall and the O'Meally's and other frequent visitors associated with bushranging.

|

Diggers at work c. 1862.

(Coloured by Me)

Courtesy NLA. |

In early 1863, Lambing Flat was still a booming goldfield with thousands of diggers scrounging the elusive metal. For Ben Hall, although notorious by reputation, was not as well known by sight.

Whereby Hall no doubt blended in smoothly amongst the large mining populace. An article was printed on the state of the goldfield demonstrating the easiness with which Hall could mingle amongst the multitudes while also conducting highway robbery at will against hard-pressed miners and storekeepers living in a rough and ready environment:

The total population numbers between four and five thousand, sufficient to support a large township if they were in any way centered or habituated within a reasonable distance of each other; but such is not the case. The population is scattered over a great extent of country, reaching (east and west) from Wombat to Blackguard Gully, a distance of fourteen miles, and from Back Creek to the last new rush (north and south) a distance of eighteen miles. This includes the whole of the Burrangong diggings. The diggings north of the Main Creek-consisting of Back Creek, Wombat, Little Wombat, Stoney Creek, Spring Creek, Victoria Gully, and Petticoat Flat were the first worked, and may now be said to be deserted; the European population generally working on the south side of the creek,-either on the Main Creek, Chance Gully, Three-mile Bathurst Hood Rush, Five-mile Bathurst Road Rush, Tipperary Gully, Duffer Gully, Hurricane Gully, or the last rush, named the Twelve-mile Rush.¹¹⁸

Furthermore, the miners were well aware of Ben Hall’s presence, even if they were uncertain of his exact appearance. Many were at their wit’s end following the most recent acts of violence committed by Gilbert, O’Meally, and for a short time Fred Lowry. They were stunned by the impunity with which these bushrangers wielded their six-shooters.

Justice seemed a distant notion as men toiled for hours—sometimes days or weeks—through dust, dirt, and mud, all for a few specks of gold or the rare euphoria of a Eureka strike. Their reward, won through backbreaking labour, was too often snatched away at gunpoint. To be accosted at the barrel of Ben Hall’s revolver, after such relentless effort, was an insult beyond measure. Hall had no regard for their toil; if need be, he would shoot a man dead as a crow. The miners’ frustration was encapsulated in their frequent cry: "Where were the police?" Their anger was justified—robbed without adequate protection, they had every reason to demand justice.

No honour could be found in a man like Ben Hall, who, through fear and violence, stripped away the hard-earned rewards of those who laboured with blood, sweat, and tears. It was enough to make any man's blood boil, not just the miners'. In response to Hall’s recent depredations, a general meeting was called at the Burrangong Gold Field on July 4, 1863, at 3 p.m., to petition Colonial Secretary Cowper’s New South Wales Government for stronger action to defend their lives and property.

The present position of this gold-field demands the instant attention of every inhabitant. An appeal to the Executive would be, no doubt, answered, and new dandies and new horse marines be sent, but these are not wanted. It depends upon the people to organise what is needed, they at least, in their selection will not abuse patronage, or count on prostituted votes. To meet this emergency, and exterminate these murderous Ishmaelite’s, we doubt not that good men and true will be found in our midst, who by this last outrage will be simulated to provide, at their own cost, a remedy, and leave us not even the opportunity of thanking the present administration.

So frustrated were the correspondents over the police's lack of information and the general malaise amongst the troopers. An editorial covering the last few months of Ben Hall's activities was published and countered much of the misinformation from authorities. (See the link attached below.)

Empire

Saturday 4th July 1863

YOUNG.

However, from the above articles glossing over it became apparent that the miner's subtle message demonstrate that the Lambing Flat goldfield populace had lost faith in the NSW Legislature. Therefore, a new vigilance and determination to extirpate Ben Hall's depredations were rising. The miners implied that they will take matters into their own hands by lynch law if their demand for punitive action and a better effort from the NSW police was not brought about. The debate led by prominent locals highlighted the fact that:

No person could leave his tent to go to a rush without being almost certain to be stuck-up and if he showed fight would perhaps be murdered. This feverish state of existence cannot be tolerated much longer.

Ben Hall, regardless of the miner's agitation, continued holding the roads and three days after the miners meeting on the 7th of July, 1863, Captain Zouch arrested two men who were in Ben Hall's company during a recent robbery:

Captain Zouch returned this afternoon, after being several days in the bush. He brought with him two men, who, in company with Ben Hall, had stuck up and robbed some teams on the Lachlan Road on Saturday last, 4th July 1863. Tuesday, July, 7th.—Chambers and M'Carthy, the bushrangers, were charged with sticking up, near Yass, were, brought up by the Police office, and remanded until tomorrow for further, evidence.¹¹⁹

Chambers was the former police constable dismissed in May, with Neilson, who it must be remembered, were the two troopers who had the gunfight with an Emu named Joe. The irony is that Chambers fell into crime with the very man he thought the Emu was, Ben Hall. Chambers was sent down for Highway Robbery, three years of hard labour.

|

Captain John McLerie

Inspector-General

of Police.

c. 1862 |

By July 15th, whilst bailing up travellers around Burrangong in the company of various miscreants, Ben Hall learnt that his archenemy, Sir Frederick Pottinger, had arrived at Young in time for another local race meeting:

Sir F. Pottinger arrived here this evening from the Lachlan. It is reported that two Chinese were stuck-up near Back Creek, but there are no other particulars about the robbery.¹²⁰

With Pottinger's arrival at Young, Hall withdrew to the remote back country of Mimmegong station. Sir Frederick Pottinger in constant contact with HQ in Sydney, forwarded the following telegram to the Inspector General’s office regarding his arrival and of the matter of the impending miner's petition, where he fibbed about the numbers present. Nobody wants to be seen in a bad light:

Arrived here last night at half-past six. Mr Zouch and Mr Singleton out with party since Thursday last, and not yet returned. I am unable as yet; and until Mr Zouch's return, to report fully to the Government on the state of the district. No report of any outrage has been received since my arrival; Saturday and Sunday have hitherto been favourite days for sticking up. A meeting was held yesterday at the Twelve Mile Rush-about 120 present-at which it was resolved to draw up a petition for signature by the miners, to be forwarded to the Government, relative to the prevalence of crime in the district.¹²¹

Consequently, Pottinger’s presence forced Ben Hall to depart his living arrangements with Susan Prior. Hall headed into the bush to Memmigong station to await the pending rendezvous with Gilbert and O'Meally Whose return had no doubt been bush telegraphed to Hall. Unknowing that Gilbert and O'Meally had recruited two new members John Vane and Michael 'Micky' Burke, to their merry band.

Furthermore, the wretched life Ben Hall had adopted in 1863 was summarised in the 'Sydney Mail' and gives a fantastic insight into his grim life outside the warm embrace of society which not only Hall but his contemporaries were suffering.

Bushranging seems to be as rife as ever, at least so far as Gardiner and Gilbert and their followers are concerned. These scoundrels move from place to place, helping themselves wherever they go, and always successfully eluding pursuit. They are a great nuisance to the country as well as a great disgrace. Yet they are not to be envied even by those who are dazzled by a display of mock heroism. To be hunted about—never able to stay long in the same place—to be always in fear of treachery—to know none of the enjoyments of civilised life, none of the comforts of home—to be alarmed at the sound of every unexpected tread— to have no livelihood except what comes from fresh robbery, and to be always in danger of a struggle which may end in murder—this can hardly be a very jolly life. No doubt they are pretty well conscience hardened and try to cheat themselves as men in their circumstances will do. But in the bottom of their hearts, if the past could be all wiped out, they would be glad enough to be in a position to get honest wages by honest labour—to return to that enjoyment of society from which by their crimes, they have cut themselves off.¹²²

Unfortunately, a reversal of fortune was now out of reach for Hall, and with the onset of winter, the bitterly cold nights would have made the outdoors most uncomfortable for the bushranger; therefore, a remote Sheppard’s hut or cave would be a welcome relief:

Winter is now fairly upon us, and during the last week we have had the first instalment of snow, accompanied by a bitingly cold wind, and all the catarrhal afflictions such a state of weather usually induce.¹²³

Venturing out from Memmigong the following report appeared of a robbery at Possum Flat, Young on Monday 13th July, which after the recent arrest of Hall's two mates the bushranger was reported acting alone and in a desperate state for cash for his harbourers:

MESSRS. Throsby and Murphy were stuck-up this afternoon, on Possum Flat, near this township, by a man supposed to be Ben Hall. Fortunately, they had no money with them. The bushranger only exchanged his saddle for Mr Murphy's, and complained of the hard times, stating that he was very hard up, from the fact that no one now-a-days carried any money with them.¹²⁴

However, Pottinger’s presence had now become a hazard for the sticking up trade. Hall's comment on the lack of ready cash also alludes to the success of the 'Money Order' system. A system for the transfer of cash throughout the colony was starting to bite. This lack of cash being born by travellers was now impeding Ben Hall. After all, his need to pay his harbourers was ongoing.

|

Captain Zouch.

c. 1860 |

The two men captured earlier by Captain Zouch on the 6th July were subsequently named, including a court appearance of Ben Hall's earlier accomplice, young Jameison:

Jamison, Smith, and Simpson - the latter two apprehended by Captain Zouch for sticking up drays in company with Ben Hall have been brought before the police court and remanded.¹²⁵

Furthermore, speculation was raised as to the whereabouts of unsighted Frank Gardiner and indicates the reporter had good sources and states finally what was now widely believed, that Gardiner had departed NSW:

The letter would not be perfect were I not to make mention of Gardiner. It has been the rule for many months to head paragraphs in the various country newspapers with "Gardiner and his gang", without any wish to shield Gardiner or the vagabonds who have committed these robberies, I think, if the fact is ever proved as to the whereabouts of Gardiner, it will be found that for at least the last nine months Gardiner has never been in New South Wales. This statement may astonish many, and without wishing to appear particularly knowing in these affairs, such I believe to be the case.¹²⁶

This also appeared:

It is said that Frank Gardiner is in California. As we hear nothing of his exploits now I suppose he has left the colony, but I don't believe anyone knows where he is.¹²⁷

Gardiner's fame knew no bounds when this was reported from The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser:

Drunkenness. -An aboriginal, who gave his name to the police as Frank Gardiner, but who, on being brought before the bench at West Maitland, on Tuesday, changed his name to Frank Edwards, was cautioned against drinking to excess, and discharged.¹²⁸

Bush telegraphs for Ben Hall were still as pivotal as ever, as per this statement in Parliament on the use of those telegraphs and harbourers:

Their own community supplied the machinery by which these depredations could be planned and executed, property disposed of, and felons concealed. Their command of horses presented no ground for suspicion, and their familiarity with all the byways of the country gave them an advantage over any strange constabulary however active or skilful they might be. They were enabled to establish a bush telegraph which, by signals known only to the initiated, could secure the more active members of the commonwealth of thieves from pressing danger. We have heard of one contrivance which will remind our readers of signals of the most ancient times. A boy upon a horse is dispatched to a certain place for some trifling object. He is not trusted with the secret of which he is really the bearer, but as he passes in a certain way, or upon a particular horse, the bushrangers understand that the road is or not clear for their operations that the constables are present, or that they are gone. Thus, by various signs and tokens, the people who were entitled to be unsuspected are really the most effective abettors of robbery and pillage.¹²⁹

However, the bush telegraphs were a problem for the authorities. Many others from the upper echelons of Sydney society held a widespread belief that some of the larger squatters in the troubled districts were complicit in turning a blind eye. To the point of even supporting bushranger activities to minimise exposure to raids by not reporting some horses and equipment losses. These perceived scoundrels were also thought to be journalists as well as Parliamentarians who for one reason or another were soft in their censure of the rogues: